Small Town Racism

Survey shows that racism, xenophobia, Islamophobia, and anti-Semitism are far from being eliminated in Bergen County.

June 18, 2021

2020 brought issues of racial and religious prejudices to the forefront of many discussions, largely due to the fact that the events of the year made it increasingly more difficult to ignore those problems. Hate crimes against both Jews and Asian-Americans spiked in 2020, according to data from the ADL Tracker of Anti-Semitic Incidents and the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism, breaking records that the year prior had set. Furthermore, with the videotaped murder of George Floyd spreading across social media, many white individuals began to acknowledge issues like police brutality and systemic racism, while many people of color gained more of a platform to voice their personal experiences with racism and discrimination that they had personally endured.

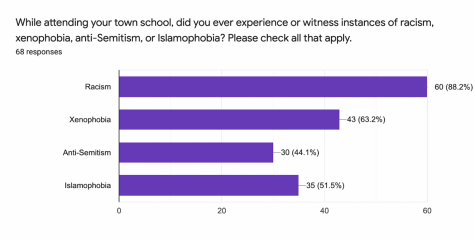

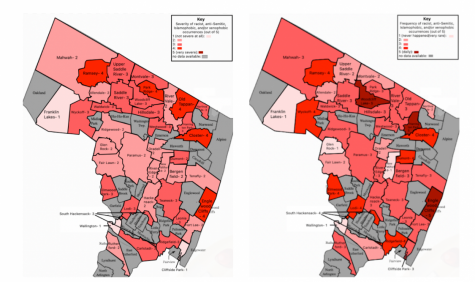

In Bergen County, issues regarding race and religion remain prominent, despite many towns parading messages of inclusivity and acceptance of all. In a survey of 79 BCA students representing 42 towns, there were only two towns where none of the students surveyed from that town had ever witnessed or experienced instances of racism, xenophobia, Islamophobia, or anti-Semitism. Eighty-six percent of students in general had witnessed or experienced one or more of those things, with racism being the most prevalent.

Interviews of BCA students show that these issues may take many forms. In predominantly white towns, many students of color felt that their negative experiences were primarily due to other students having a lack of exposure to other cultures. For instance, of the two students surveyed from a town with a white population of 71.3%, according to DataUSA, both rated the frequency of racism and/or xenophobia as a daily occurrence, but averaged only a 2.5 out of 5 when asked to judge their severity.

“Racist comments are thrown around all the time, but they aren’t seen as that bad for some reason,” one of the students explained. “Everyone just accepts it and doesn’t get (openly) offended. That’s just how it is.”

The other student from that town explained that much of the racism and xenophobia was not intentional. “One of the main things that I personally encountered was xenophobia in food and food choices,” said one student. “I definitely saw the stigma around bringing certain foods to the cafeteria because kids would just blatantly judge you while they had very American lunches, like chicken fingers and whatever, so… I didn’t bring Korean food for lunch… You didn’t want to go through the extra hassle of bringing your food and knowing that you’re probably going to get some judgement for it.”

However, the student explained further: “It doesn’t even feel like, for those kids, they’re actively thinking about what they’re doing when they’re being so openly xenophobic towards other people’s food…. and that probably just comes from the way they were brought up, or the way they weren’t brought up– just the lack of exposure to other cultures.”

Similarly, this student added that many students used the n-word, despite there not being any Black individuals in their grade. “And from my sense of it,” she said, “I think a lot of it was a clear ignorance. The way they were using it wasn’t even as a means to oppress Black people because there were no black people in sight. It was just a way to throw around and abuse the term because you don’t actually know the roots of it. At such a young age, being exposed to it and having the misperception of it, and then just throwing it around because you don’t know any better… because nobody checks you [and] nobody ever called anyone out on it, ever.”

A student from a nearby largely white town had similar experiences, although they “don’t think that [their] middle school was racist. Much of what they saw was, in their opinion, conversational, casual, open hate, like people walking down the hallway and chanting something, often against Black, Asian, and Muslim people.

“I remember how it feels to hear it- first the wave of disbelief and disappointment that the people who you call your friends would utter these words, as you ask yourself why. Maybe they don’t know how much it hurts, you tell yourself, maybe they don’t care… And the room is filled with silence as you struggle for the words to say. Maybe silence speaks louder than words, sometimes. But later on, and months afterwards, you’ll think about that day and about what you wish you would have said.”

Derogatory comments about race continued in another largely white town. “They didn’t really care about marginalized communities’ feelings or POC feelings,” said a BCA student. “Like, I feel like Indians are the meme of the races– everyone’s making Indian accents and they think everything we do is funny, even though it’s serious, so I remember a lot of people would obviously do the Indian accent to me or ask if I wanted curry, and I mean that was pretty normal. I didn’t even think that was racist back then. It was so normalized.”

In contrast to the other BCA students from predominantly white towns, though, this student did not eliminate the possibility that these comments were intentionally racist. As opposed to the experiences of other students arising out of soleley ignorance, this student felt as if his classmates believed that “non-white people are side characters or a joke they can make fun of.”

The idea that microaggressions resulted from a “heavy lack of exposure” and “child ignorance”, in the words of a student from a majority white town, persisted in many other places. On the other hand, one student from a town with a white population of 46.8% and an Asian population of 41.8% said that racism and/or xenophobia were daily occurrences, rating their severity as a 4. However, this diversity was not accurately represented at the school, which the student felt was still predominantly white. “There were no Latinx or Black students in my grade in elementary and middle school, which I believe contributed to the racist mindsets of the predominantly white student body.”

Prejudices against different religious groups also exist in many towns, although, according to the survey, at a lower rate when compared to instances of racism or xenophobia. 44.1% of students witnessed/experienced anti-Semitism and 51.5% witnessed/experienced Islamophobia. In some cases, it appears to come from a place of malice, rather than the mere ignorance that previous students cited as the main reason for most racial microaggressions.

For example, one student from a northwest Bergen town said, “I just had to deal with antisemitic stuff in seventh and eighth grade. One kid had it way worse and ended up switching schools because kids kept on doing the Hitler salute to him. For me, one time, I was in line for some game in Gym and this kid said something like, ‘Get to the back of the line, Jew.’ I also would hear a lot of kids yelling about gas chambers on the bus, and I once went hiking with someone from [the town] and he showed me swastikas that he had spray painted on a rock, but he told me not to worry because I was a ‘good Jew’.”

Similarly, one student from a southern Bergen town said, “I mostly had to deal with Islamophobic jokes from my ‘friends’.” In another northern Bergen town, even some authority figures promoted Islamophobia. One BCA student explained that a fifth-grade teacher from her town had described 9/11 in a way that had made the one Muslim girl in the class feel “uncomfortable,” but that the teacher did not apologize or make an attempt to better educate herself or the class, despite the fact that the girl’s mother had talked to the teacher and explained the issue with the lesson.

The student explained: “I feel like, in such a homogeneously white [area], it’s just that the teacher didn’t do a good job of saying it in the first place, and the fact that she’s a teacher and didn’t correct it just made it worse. I think part of it is not explicit Islamophobia. They’re not saying, ‘We hate Muslim people,’ but there is a kind of a bias, and also an ignorance of this other culture in general, just because most people are American and white.”

This student also personally experienced the effects of the “ignorance about other cultures.” For example, she said, “One of my friends wouldn’t stop making ‘ching-chong-ding-dong’ jokes at me. I don’t know why, just felt compelled to say that to me, even though I said it wasn’t funny, and I feel like he wasn’t trying to be mean, just trying to be funny.”

In some cases though, this racism, xenophobia, anti-Semitism, and Islamophobia took on more dangerous or harmful forms. “The children were never racist, but the adults, especially the police, were,” says one student from an almost exclusively white town. “They would pull over two darker-skinned people (my mother, who is Indian, and one of my sister’s friend’s mothers, who is Puerto Rican) for ‘parking violations’ at school drop-off and pick-up nearly every day, even though they were rarely doing anything wrong and, if they were, literally all of the other Caucasian parents were doing the same thing but never faced any repercussion.” With stories on police brutality frequently appearing in the news, it is important to examine the implications and potential repercussions of these “parking violations,”even if no one was ever overtly harmed.

One student from a predominantly white town also explained the fear that some people of color have, even in relatively mundane situations. “Both of my parents are Asian,” the student said. “There are days where I like taking walks or bike rides or stuff outside on my own. I’m scared of every single person I pass by. I know of hate crimes that happened in towns near mine, towns that I’ve walked through before. Chances of one happening in my own town seem slim, but these days you never know. And maybe I could be overthinking every glance or judgmental look or cautionary whisper, but the issues going on have been too prominent to get out of my head.”

A statement by a student from a heavily white town showed the presence of this anti-Asian sentiment in their town, and the ways in which it escalated past verbal abuse. “In 2020 a Chinese restaurant was vandalized with racist graffiti relating to the COVID pandemic,” they said. This story is just one example of the many physical attacks against Asian and Pacific Islander (AAPI) individuals that occurred in New Jersey throughout the pandemic. New Jersey as a whole experienced the highest number of Anti-Asian “bias incidents” in 2020; a report by the NJ state police showed that reported attacks against AAPI individuals rose to 71 in 2020, an 82% from the 39 incidents that occurred in 2019.

This past year has brought discussions of these issues to the mainstream media, with a large emphasis on these more subvert and under-the-radar acts of racism. However, according to public health officials, these events’ ambiguity and unobtrusiveness should not be equated with them lacking any significant consequences. A 2018 study in the Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, of the clients who had reported race-based trauma to their counselors, 89% identified “covert acts of racism” as a contributing factor. Public health officials are also starting to identify ways in which microaggressions, especially when frequent and long-term, contribute to higher rates of mortality and depression.

Furthermore, as Chester M. Pierce, a Harvard University professor who first coined the term “microaggression” in the 1970s, wrote, “It is the sum total of multiple microaggressions… that has pervasive effect to the stability and peace of this world.” Thus, the microaggressions that BCA students experienced, usually in largely white environments, have the potential to accumulate into what seems like a constant stream of insults in the eyes of those being hurt by those comments. Not to mention, as shown by the stories of some students, racism, xenophobia, Islamophobia, and anti-Semitism also exist in Bergen County in the form of macroaggressions, which are the more severe acts of racism like the anti-Asian graffiti or spraypainted Swastikas. Regardless, working to eradicate microaggressions from popular culture and common dialogue— especially if they do not necessarily affect you directly —is, by definition, integral to rooting out exclusionary habits that make people with different races, cultures, ethnicities, or religions feel like “others”. In the words of former First Lady Michelle Obama, “If we ever hope to move past [race and racism], it can’t just be on people of color to deal with it. It’s up to all of us — Black, white, everyone — no matter how well-meaning we think we might be, to do the honest, uncomfortable work of rooting it out.”