Data Journalism Edition: Can Women Lead? Skewed Ratios Persist Across Professions

Arianna Huffington, a board member of Uber and founder of Huffington Post, recently stated during a board meeting that having one woman on a board usually encourages more women to join. In response, another Uber board member, David Bonderman, said “actually, what it shows is that it’s much more likely to be more talking.” The exchange revealed the hostility that women on corporate boards sometimes face–and caused Bonderman to resign.

In the United States, there is low female representation in leadership positions at just about every level of society, whether it is in the government or in schools. Many factors play into the dearth of female leaders at a national level. Yet these low numbers are unfortunately seen at a local, Bergen County level as well.

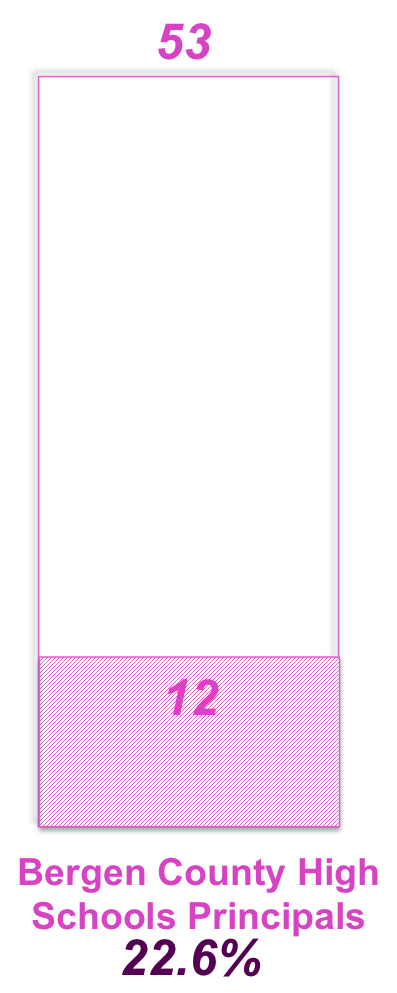

The percentage of Bergen County high schools led by female principals is a mere 22.6%. With just as many girls in school as boys, the administration should arguably reflect the student body.

In Bergen County Academies itself, 55% of the student body is made up of female students. In other words, boys make up less than the majority of the student body, yet men make up more than the majority of the administration.

Bergen County Academies lead teacher Heather Lawler recalls that when she was growing up, “women were always teachers in the classroom and men were always part of the administration.”

Yet Ms. Lawler explained that over the last 45 years, “women are at least considered; women are now at least included in the applicant pool. Yet I truly wish that the administration would match the student profile of our school, which is 55% female, and give girls and other minorities, and people, the opportunity to see leaders that reflect their image.”

Fortunately, Ms. Lawler has seen improvement even within our small Bergen County community. She expressed her happiness especially in the senior internship program, saying, “I have been working here for 13 years. Within those years, I have seen a shift in female participation in those who participate in internships involving computer science and the financial sector. I used to have to beg a female student to grab opportunities in those fields, but now they have become one of the most competitive fields in female representation at our school.”

It may seem that the dearth of women in leadership positions is a result of gender discrimination in higher education.

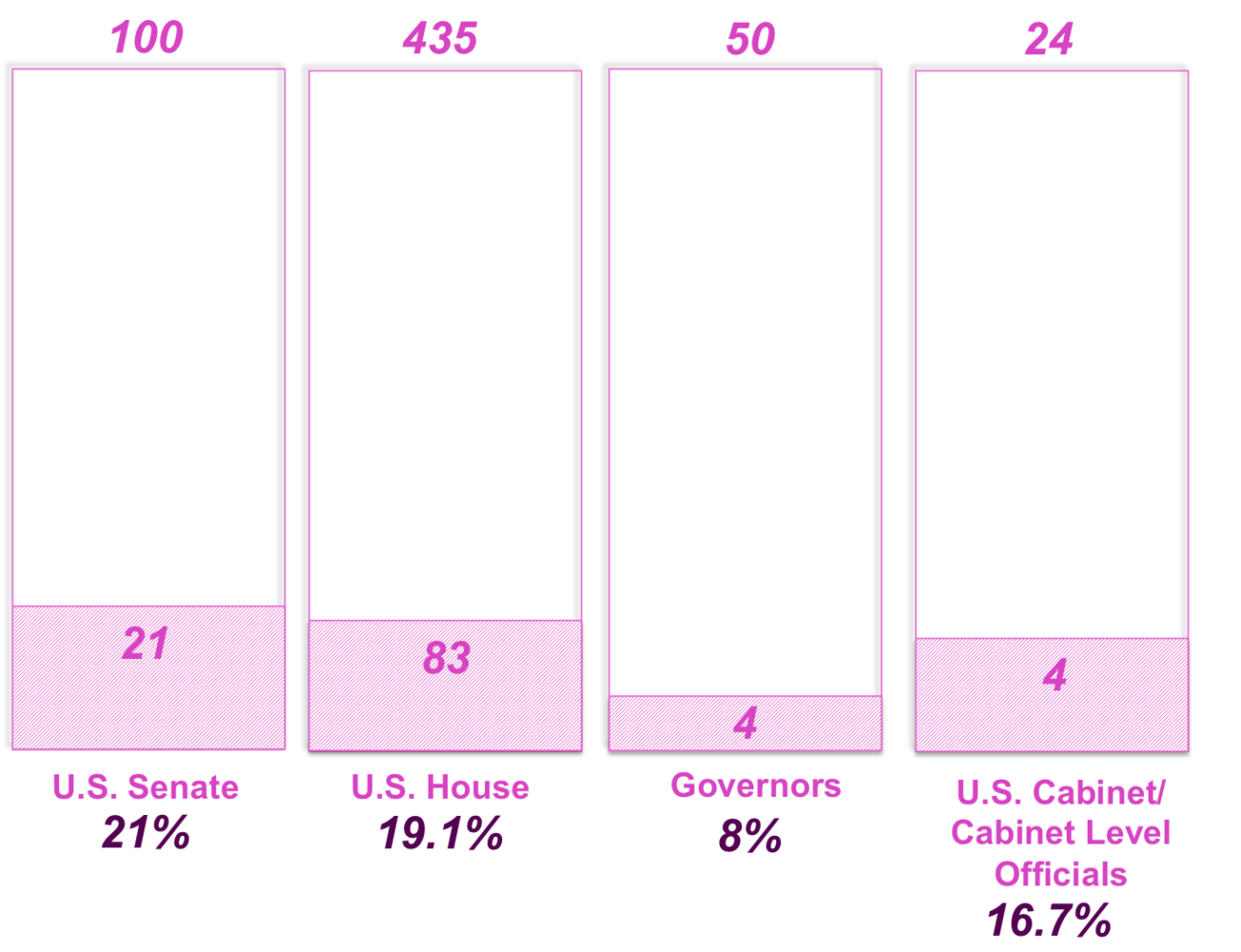

Even in federal service jobs, between the U.S. Senate, the U.S. House, Governorships, and the U.S. Cabinet, female leadership is overwhelmingly low.

A mean of 16.2% of the total seats are occupied by women. In a genuinely impartial society, women should occupy 50% of those seats. Of the fifty governors that lead the United States, 4 are female: Mary Fallin (R-Okla.), Kate Brown (D-Ore.), Susana Martinez (R-N.M.) and Gina Raimondo (D-R.I.). As for the cabinet and other related officials, numbers have actually been dropping by the year. The highest female representation in the cabinet was 40.9% during President Clinton’s second term (1997-2001).

Although overall numbers of women in leadership positions have been on the rise since 1967 to 2017, the 16.2% statistic shows how slowly the rate of female representation is growing.

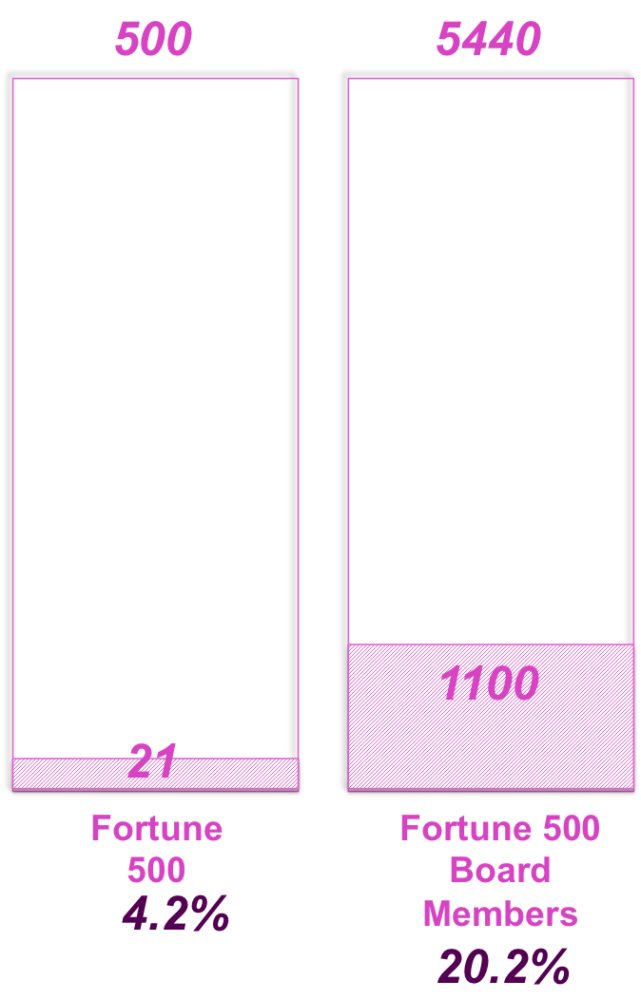

Fluid graphs were purposefully chosen for these data representations.With the fluid graphs, regardless of the total number of seats in the government positions, all of the data bars are equal heights. Each female representation percentage only fills up a small percentage of each bar’s area.

The rest? The rest is white space. The rest is male representation.

Corporate America does no better than the government in hosting female leaders. Women make up 50.8% of the United States population, which is more than the majority. Yet only 4.2% of the United States’ corporations are led by a woman. Just 21 of the 500 companies making up the Fortune 500 are led by a woman. In 2015, 24 companies were headed by women in the Fortune 500. The numbers have since dropped.

Oddly, though, the gender gap in the corporate world is not directly correlated with the gender gap prevalent in college. Studies by Dr. Michael W. Kirst show that women have a higher college graduation rate than men, with women at 32% and men at 22%. Women have also been successful in earning more degrees than men, a trend that started in 1978 when women started to gain more Associate’s degrees than men. By 1987, women earned more Master’s degrees than men and by 2006, according to Kirst, “female domination of college degrees at every level was complete.”

So how do women fail to achieve the same success they execute in college when they are in the workforce? Is it the result of trying to juggle a career and motherhood? Women constantly face challenges in attaining a high status in any career, and this fact is not only supported by the previously pictured fluid graphs.

Ms. Lawler was asked about this topic. When asked if she ever felt as though she had to refrain from advancing her career due to motherhood, she replied, “like most women, there were definite times when I did hold back. If I was looking for a job opportunity, I would limit myself geographically, finding jobs in which my son would not have to change schools, and always put his needs ahead of mine.” Later Ms. Lawler shared that she decided “to move out of human resources recruitment to education so she could be more present” with her child.

Additionally, Sally Hubbard, a legal journalist, published a recent article on Slate, mentioning that her career boost was not due to a promotion or a pay raise but was a gift from her husband. The gift: her husband left his job at a law firm to work from home. Unsurprisingly, this had many benefits. Hubbard no longer had to carry the burden of the stereotypical housewife: doing laundry, preparing dinner, and watching over the kids every moment of her day. Hubbard’s husband started to cover everything. The result? Hubbard has been released from the parenting labor she was engaged in, and could now reach new heights in her career.

The idea of motherhood affecting women’s work was first noted by author Arlie Hochschild. In her landmark book, The Second Shift, published in 1989, Hochschild observed a clear difference in unpaid labor for married women. Hubbard mentions that “With a reduced mental load, I have reallocated the gained mental space to my goals… I have begun speaking on panels instead of sitting in the audience watching mostly male speakers talk about topics I know as much or more about.” Hubbard knows that other females would have a life similar to her own, for studies show that women seek more flexible, and thus lower paying, jobs to account for motherhood, causing the gender gap.

An endless number of studies support Hubbard’s theory. Studies show that “when women reach their 30s, many start having children, and—whether as a direct result or not—some drop out of the workforce altogether.” Women often have to choose between motherhood and success at work.Pew Research revealed that 74% of women believe it is easier for men to get top executive positions and 73% of women believe it is easier for men to get elected into high political offices.

Why do women give into these stereotypes? It may be due to the fact that, despite the disparity of women in the workforce, research shows that 61% and 58% of men and women believe it easier for men to reach to reach C-Suite positions and powerful political positions, respectively. How can women reach their full potential in public representation when their male counterparts don’t push the barriers of these absurd stereotypes? The effort for equal women’s labor may require more women to obtain the independent “Hubbard lifestyle”.